Dale Marsden's ABJ Story

Edited by Mary Weaver for the American Bee Journal June 2016 issue

Dale Marsden has "worn a lot of hats" in his varied, busy careers, but the one consistent thread through it all has been sideline beekeeping. Drafted into the US Air Force immediately after graduating from college with a degree in physics and math, he stored his equipment and left only a few hives of bees on his father's farm and went flying for the next seven years. While stationed at an Air Force Base in South Dakota, his "bee withdrawal" was severe enough that he sought out then-South Dakota commercial beekeeper Alvin Zeitlow, who helped him to set up some hives near the air base. Trained as a Navigator, Marsden flew bombing missions in Southeast Asia and pulled alert duty in SAC (The Strategic Air Command). After contracting Hepatitis A, probably from a mess hall, he was sidelined from active duty. While he was recuperating at the hospital, his brother helped him to place 70 hives he had purchased. That winter half of them perished in deep Wisconsin snowdrifts. Undeterred by the punishing losses, he ordered more packages the following spring, and has been a sideliner with about 50 hives ever since. All the while, he worked 40 hour a week jobs in industrial engineering and later in physics (making components for particle accelerators) in addition to simultaneously serving in the Wisconsin Air National Guard, and later in the Reserves, where he also flew cargo missions for the first "Gulf War" in the Middle East. He retired from the Air force in 1992. He also serves his community as the president of the local historical society and is active in the McFarland Lutheran Church. "I liked that I could have a career and also run a beekeeping business on the side, getting some extra income and the tax advantages, while doing something that I've really enjoyed since I started keeping bees as a 4H project with my brother when I was 16."

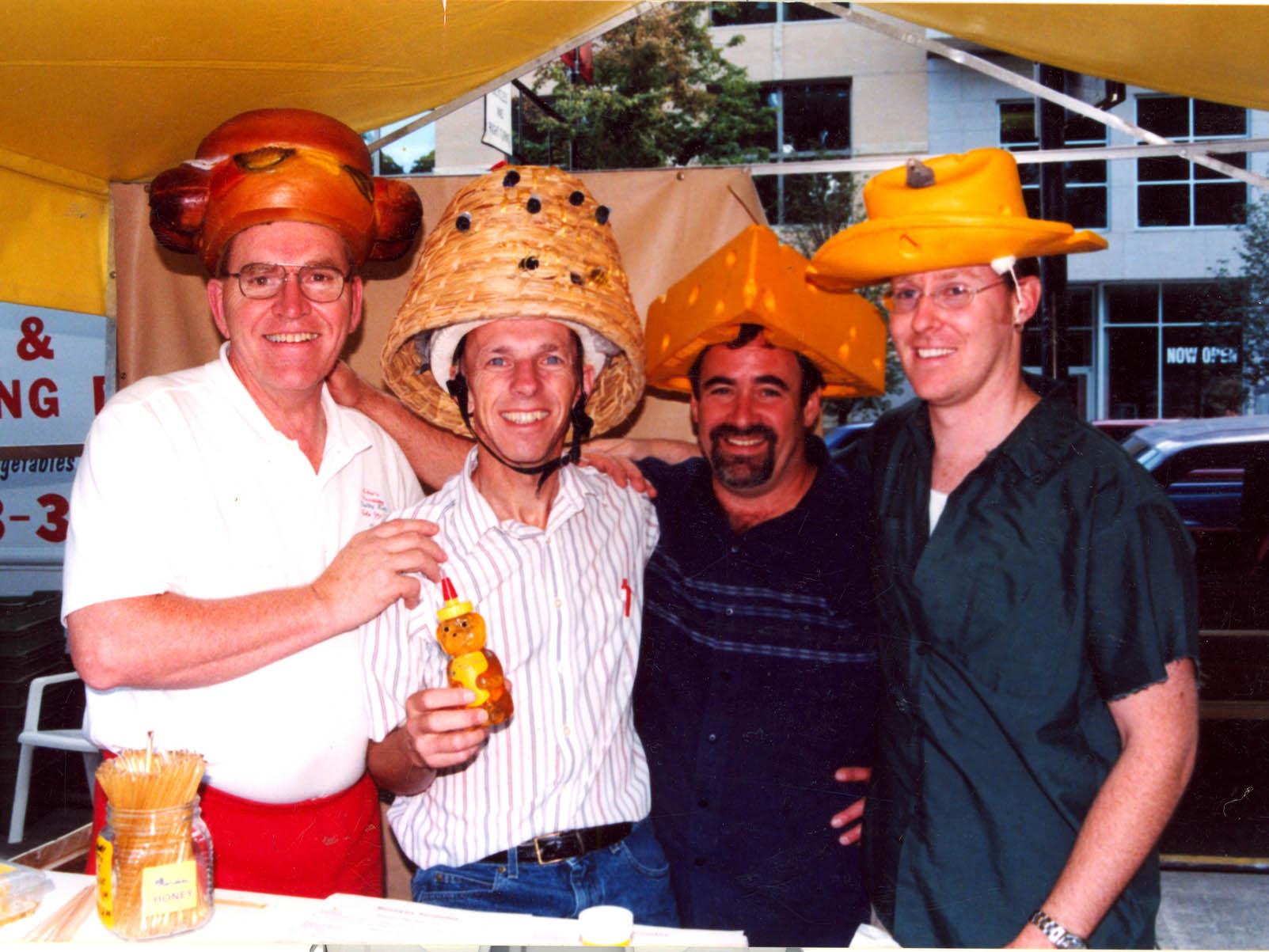

During his long career as a sideliner, Marsden has always sold his honey bottled and his beeswax made into candles, figurines, and wax blocks. Part of the enjoyment of beekeeping for Marsden has always been the direct marketing. For a time, he was marketing his honey and beeswax at 5 farmers markets. Although he only markets his honey and beeswax products at the huge Dane County Farmers Market, now a Wisconsin producer-only market, at the age of 69 years young, he has no plans to cut back on his beekeeping or marketing for at least the next 5 or 6 years. After a lifetime, being a sideline beekeeper is an integral part of who Dale Marsden is! Over the years, Marsden has learned a lot about successful marketing, beekeeping, honey production, and ways of keeping his bees alive through Wisconsin's long, frigid winters. Marsden's Marketing Tips :

• "If you sell at farmers markets [or festivals or fairs], find a way to make yourself stand out that emphasizes that you are a beekeeper selling your own honey." Early in his career, Marsden accomplished this by creating skep hats. "My customers have a fit if I show up at the market without my skep hat," he chuckled. "Particularly if there is more than one beekeeper selling at a given farmers market, the skep hat gives a sales advantage." Marsden has made two. He first made his large one, and later made a somewhat smaller version "that is easier to wear."

• "Customers like a choice." It would certainly be simpler to extract all his honey in one or two big batches and sell it all as Wildflower. Instead, Marsden extracts small batches of honey frequently, keeping floral sources separate, so that most of his honey can be sold as varietals, each with its unique individual flavor: light, delicate star thistle (knapweed) from northern WI; dark but mild-flavored smartweed; lemony basswood; dark, rich-flavored goldenrod; mild-flavored clover; occasionally buckwheat, which has a bold flavor and a small but dedicated clientele; cranberry from his cranberry pollination, and others.

• "Selling raw honey attracts customers, and can bring higher prices in many places." To make sure his honey is not overheated, and can be truthfully called 'Raw,' Marsden no longer uncaps with a heated knife, as he used to before he designed the heater/blower that heats his honey in the combs in the supers. "I used to use a heated knife, but the temperature regulation wasn't the best, and sometimes the hot knife would darken the cappings honey," he explained. With the heater/blower, the combs are warmed enough (to 90 to 95 degrees), so that I can uncap with a serrated bread knife.

• " Many customers are looking for comb honey and chunk honey, and are willing to pay very good prices to get it." Not very many beekeepers are producing comb honey these days. Getting the frames ready is time-consuming, and if your honey flow ends early for some reason, you may not get much comb honey for your efforts. "I usually put on about 30 comb honey supers, and get about 20 nice, full supers," Marsden continued. "The combs that aren't completely filled out can be cut in pieces for chunk honey, which I sell in two sizes, as long as most of the cells are capped." "I use 7/11 foundation which the queen doesn't like to lay in. Attached at the top with a nailing strip the foundation should not touch the bottom of the frame. The bees stretch the foundation and if it is touching the comb sags to one side as the bees build the comb. "Before putting in new foundation, each year I carefully scrape and clean up my frames. When the frames get old, I wire them, and use them as combs for extracting." Marsden's bees on star thistle have made beautiful light comb honey that is slow to crystallize, with bright white cappings. "I always sell out of comb honey long before the next year's crop is ready. Chunk honey also sells out quickly at farmers markets." • "Customers appreciate samples." Marsden offers samples of any of his products to anyone who asks, using a wooden tea stirrer. "This really spurs sales of spun honey (in 3 sizes) and comb honey, because many people have never tried them before."

• "Design your own attractive labels that include the honey's varietal name." Marsden designed his own labels, and has been using them for many years. For a while, Marsden was giving his farmers market customers a choice of 5 sizes of honey bear: Mama, Papa, big brother, baby bear, and Minnie bear. Now he stocks 3, each with a custom-designed label. The smallest is a 2-ounce bear, which he wisely named "Travel Bear," to emphasize to the many tourists who come to the Dane County Farmers Market that the tiny bear is a good souvenir item. How you name your products can make a big difference in sales!

• "Keep your market stand neat by using a stand to hold fast-selling items, like honey bears. I designed the hex-shaped stand to hold the bears." ( See photo) The stand is also eye-catching, and adds some height to his display. "Originally, I had designed it to be made entirely of Plexiglas, but then I would have had to get all professionally-cut parts. I made the shelves three different sizes, and redesigned the top and sides to be wood. "I asked a carpenter friend to make the top and sides from wood, with cross braces on the bottom to hold them all together. My bear stand does not rotate, but it is easy to move the bears up to the front, and makes me look a little busy when customer traffic slows." • "Special packaging can help you to sell honey for wedding favors, bridal showers, and baby showers." (See photo) Marsden sells wedding, shower, etc. favors in three containers: a 2 oz. hex jar with a gold lid, a 2.5 oz. plastic jar, and the 2 oz. travel bear. Orders are usually for 100 or so, and you can make a good price per pound of honey by going to the trouble of bottling it in small containers. "I was very busy doing 5 weddings during last August and September." As you become known for providing favors for special events, more and more customers will seek you out.

• "Specialty candles sell well for gifts and souvenirs, especially around the holidays." Year-round, votives are Marsden's best sellers, with tapers in second place. Dane County Farmers Market, where Marsden is in his 38th year as a stand holder, only allows colored candles and ornamental shapes at Christmastime, and Marsden takes advantage of this to produce some beautiful floating rose candles, teddy bears with glued on "google" eyes. ++++++

Tips on Moving Bees "Moving bees is a lot less stressful when you use a hive carrier."(See photo). If you have another person to help, it couldn't be simpler to pick up a hive and walk away with it using a hive carrier. (Ellen, a young lady from the farmers market who asked Marsden to help her learn beekeeping, is assisting him in this photo.) You can walk up a ramp to set the hive down on a trailer, no straining or heavy lifting needed. Over the years, another source of income for Marsden from his bees has been from pollination, and he still moves about 20 hives to pollinate 5 apple orchards, and moves 10 hives near the fields of one cranberry grower/friend for 2 to 3 weeks. One of his apple orchards requires several hive movings for strawberries and vine crops over an extended season, including late season, when the hives are heavier. When asked if he has ever had large hive losses from sprays while pollinating, he replied, "Never." He also moves some of his hives 283 miles north to catch the prized star thistle flow in northern Wisconsin. Although he is no longer young, thanks to his hive carrier, all these moves are no problem.

Make More Honey with 2-Queen Hives "The more you read and study about bees and beekeeping and try new ideas, the more honey your hives may be able to produce." Early on, Marsden read in "The Hive and the Honey Bee "about two-queen hives. He immediately understood the potential of the two-queen system. "I ran a number of two queen hives for many years, and they often produced more than 200 pounds to the hive on the long star thistle flow, which is a strong flow for more than 6 to 7 weeks many years. I plan to run some 2-queen hives this year too. I'll be able to raise my own queens for them, to keep the expenses down. "I divide my hives in early May, and by late June, after pollination is over, I move some hives to northern WI for star thistle. To create the 2-queen hives, I start with two equally strong hives, each with a good laying queen, with several supers on both, and stack one on top of the other, separated by a queen excluder with newspaper, which the bees will eventually chew away. "This will give me a colony with more than 60,000 workers. With a good honey flow, that many workers can bring in lot of nectar! If I would happen to lose one of the queens after the flow starts, so much the better. I already have a huge field force, which will then be augmented by additional younger bees, since, with only one queen, fewer nurse bees will be needed. Tips for Keeping Expenses Down for the Sideliner o Marsden's honey house is a simple detached garage. "It keeps the bees away from the family's house and the wife is happy." o "As a sideliner, you can extract and bottle your honey and heat and clean up your beeswax for candle making without spending a lot of money on equipment." Marsden could have afforded to invest in a stainless steel bottler with a water jacket. He did not, because he saw no need to. After 53 years of beekeeping, he still bottles from a plastic bucket with a honey gate. o "An induction heater," he believes, "is the most reliable way to warm honey enough bottle it, but still keep the honey raw."

Recently, he could have bought a new gas stove for his honey house, to use to melt his beeswax in a double boiler, at $450 or $500. Instead, he chose an Induction hot plate, which has several advantages. "First, it can't overheat. I can set it for 160 degrees, and not have to worry about the beeswax inadvertently overheating. To warm honey for bottling, I can set it for a temperature that will warm the honey, but still keep it dependably in the temperature range that is considered 'raw.' A second advantage of induction hot plates is that after 2 hours, if someone is not there to keep them turned on, they automatically turn off. " This is a significant safety feature. Overheated, beeswax can suddenly burst into flame. Many a honey house fire has been started over the years by overheated beeswax when the beekeeper turned his back or was suddenly called away. o By storing all his extracted honey in buckets, Marsden has not needed to invest in pricey barrel moving equipment. o He needs no "hot box" taking up a lot of space in his honey house. Instead, he designed and made a simple blower-box to warm his honey in the comb in two stacks of supers. "I built it from my own design 20 years ago. (See photo.) I used a milk house heater, about 1500 watts, with a fan that blows the hot air up through stacked supers. You need to remove a frame or two from each super so there's room for the hot air to pass up through them. Otherwise, if there's not much air space between fat combs, the heat could become trapped at the bottom of the stack, and the combs in the bottom super could melt if they're left too long. You want a 'chimney effect,' with the hot air passing up through the stacked supers." o "Older extractors can work fine."

Marsden's extractor is a Dadant model 440, made in 1978. "It holds 20 deep frames, or you can double up and spin 40 shallow frames at a time. I change the bearings every other year, and it's holding up well." o For separating his beeswax capping from the honey, Marsden made his own solar beeswax melter. o "For retail sales, honey and beeswax must be clean. To clean up my honey for bottling without removing the pollen grains I strain it through a 90-mesh cloth right into my bottling bucket. After several uses the cloth is used to strain wax. After beeswax has been melted to separate it from the honey in my solar wax melter, I heat it on my induction hot plate at 160 degrees, then strain it. The cloth eventually gets thrown out after melting the wax out it of in the solar melter."

As Swarm Season Slows, Plan Ahead for Good Wintering

Here are some tips for good wintering that Dale has accumulated over the years. o Good wintering yards in cold climates should have certain characteristics. "I winter all my bees on a hillside that used to be a terraced field. The coldest air drains to the bottom of the hill. A wooded area forms a good windbreak to the west, and the hillside with a wooded area on top protects my bees from winds from the north. It can really be quite pleasant in this sheltered spot on a sunny but cold winter day." o "Wrapping your hives helps them to survive in Wisconsin winters, but it doesn't have to cost a lot if you are careful how you store the sleeves over the summer. I bought my first sleeves form Dadant in 1978, and they lasted 20 years," Marsden smiled. "I folded and stacked them carefully at the end of each winter. They were pretty ragged the last couple of years, but they still did the job. "The next batch of sleeves I bought I cut off the flaps. I've found that just having the sleeves is enough. The sleeves break the wind, and their black color absorbs the sun's heat, warming the hives on sunny days." o Make your own insulation boxes. Marsden didn't invent his insulation boxes. He saw the idea on the Internet about 5 years ago, immediately understood their value in wintering bees in a cold climate, and made the boxes for all his hives. "These insulation boxes sit on top of the hive," he explained. Because all heat rises, the heat generated by the cluster when the individual bees flex their large wing muscles also rises. The insulation box traps that heat. The insulation in the box also traps, and allows moisture from the bees' metabolism of honey to escape. That moisture could otherwise condense on a cold cover and drip down on the colony, making it difficult for the bees. "To make the insulation boxes, I stapled 1/4 inch hardware cloth on one side of a super. I put row cover fabric -the kind you use for frost protection or insect protection in the garden- on top of the hardware cloth, then filled the super with cellulose insulation. Finally, cover the top of the super with metal screen or more hardware cloth. "It's also important to drill slanted holes on each side of the insulation box to allow excess moisture to escape. The insulation boxes allow the bees to keep warm with less effort and food during the bitter Wisconsin winters. The bees are also able to start raising brood earlier. (Brood rearing requires that a temperature of 92oF be maintained at the center of the cluster to keep the brood alive. If the bees run out of honey in one area, the warmth trapped above them by the insulation box MAY make it possible for them to move to other areas of the hive that may still have honey stores, or they may be able to move up to the fondant stores Marsden puts on top of the brood box for emergency food. o Here in the Upper Midwest, with extended cold winters, we have to treat for mites at just the right time or we won't have enough "winter bees" (defined as bees that have developed in late summer and fall which have built up extra proteins and fat bodies to enable them to live through the winter), so they can maintain the cluster until more brood can hatch in late winter and early spring. I treat in spring and fall. The best time to treat is when the mite population is peaking, but there is not a lot of capped brood in the hive for mites to hide in and raise their young. This can happen in late summer during a period without a honey flow when the queen may temporarily stop laying. Treating just at this time will cause the mite population to crash. Timing that fall treatment is tricky. "I generally have a few hives that die off by January because they don't have enough 'winter bees' that are not damaged by mites to live through the winter. Sometimes it can be a trade-off between giving the bees time to gather more nectar during a good honey flow and treating at just the proper time."

Consider whether electronic hive monitoring during the winter months might be of benefit in catching problems early, when hives could still be saved. This winter, Marsden invested in hive monitoring devices called BroodMinders for several of his hives. BroodMinders were developed by fellow bee club member Rich Morris and his excellent team. After Marsden purchased several BroodMinders, he and Rich Morris became friends. Soon after, Morris supplied enough BroodMinders for all of Marsden's hives. Marsden's wintering yard was a handy stop on the way home from Morris' job in Madison. Using an Android cell phone app, Morris could check on the data collected by the 8-inch plastic strip on top of the brood nest. Marsden was able to receive regular readings on the temperature and humidity of each hive on his IPad. "Rich has improved his app so you can graph the data every hour from each separate hive. He has developed a simple-to-use, lightweight bee hive scale also, and will soon be able to couple that with the BroodMinder. He is developing a relay device so no one will even have to go to the yard and get within 10 feet of the hive to retrieve the data." We spoke with Morris to find out more about his device. "The temperature monitor is accurate to .5 degrees F., and the humidity monitor to within 3% relative humidity. You'll be able to notice the slightest changes in the temperature and humidity in each hive, allowing intervention before it is too late. BroodMinder uses the latest Bluetooth, low-energy technology," continued Morris, "so as not to risk any effect on the bees. "I'd like to collect as much data from as many beekeepers as possible. Right now we have the perfect opportunity, with thousands upon thousands of small hobby and sideline beekeepers who are very interested in the welfare of their own bees and bees in general. "By performing measurements on thousands of hives, we may be able to gain insight into hive distress and develop interventions to improve the outcome. To any beekeeper who shares his data on our public repository (beekeepers are identified on the repository by zip codes), we will provide free software upgrades and data storage."

Interesting Mentoring!

Marsden's brother-in-law, Harold Risse, an accountant who sold honey from his own hives in Minneapolis Farmers Markets, changed Dale's life forever by teaching him beekeeping skills. Marsden himself has looked for opportunities to "pass the torch" by mentoring other beekeepers. Two in particular stood out when I spoke with him. Ellen, a young girl at the farmers market, asked him for help in learning to keep bees. Since then, in the Peace Corps, she herself has taught beekeeping, first in South America, and currently in Africa. The second was a bit more complex, but very satisfying as well. "A man from Uganda posted on the Internet asking for help. A member of our bee club passed his request around at a meeting. To some, it could have looked like Spam, but I went with it. I was looking for an opportunity to do some mentoring, and this was a great opportunity to do that internationally. "I emailed Isaac Semwanga, who was receiving emails in an Internet café. At this point he was a small beekeeper and had started a small bee club, the Wampiti Beekeepers Association." Beekeeping questions and answers flew back and forth in emails between the two. Isaac and his friends had been keeping hives mostly in logs, and inspected their bees and harvested honey at night, with no protection at all. They smoked the end of their log hives with a lighted stick. They learned very quickly. From a donated bee suit, they made a pattern and made their own bee suits. They asked a tin smith to make them standard smokers. They purchased wood, and made everyone a top bar hive. They even devised a 4" diameter can sugar feeder for these hives. Feeding sugar syrup during frequent dry spells helped to cut down on absconding, so they could keep bees year round. Marsden's Beekeepers Association donated money to buy Isaac a laptop, and Marsden sent a number of useful items, delivered by a church member returning to Uganda, and later by a group from the U of WI headed to Kampala, including light bee gloves, a veil, candle molds, bee books, a DVD full of beekeeping information, and a small African beekeeping booklet he had made up, in addition to the bee suit. With his new laptop, Isaac sent lots of photos, and the emails between the two continued to flow. In February 2014, Isaac's Bee Club had about 70 members, and he had already helped to start a second bee club. "He is on Facebook a lot now, and is in contact with beekeepers around the world," said Marsden. All in all, it was a very fulfilling international mentoring experience!